8 Easy Ways to Play the G Chord on Guitar

One of the first things many players learn is how to make a G chord on guitar. However, as you’ve probably noticed, a standard G chord isn’t all that easy. Sure, it’s not as challenging as the F chord, but it’s also not a no-brainer like your basic C, A, and D chords.

This post is all about providing you with 8 ways to play the G chord on guitar, all of them relatively easy. In fact, a few of these G chord shapes are easier than the first G chord we normally learn!

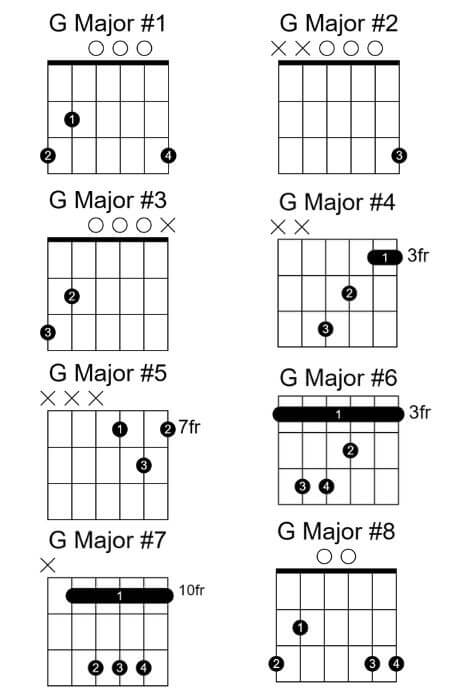

If you’re just here for a quick reference, here’s a chart of all 7 ways to play the G chord I’ll discuss below:

What's in a G Chord?

I spent years playing the G chord without really understanding what it was, and that’s probably a common experience. Many guitarists hold out on learning music theory for as long as possible, usually assuming they don’t need it or that it’s too difficult.

The good news is that you don’t need to be a genius to understand this stuff. Take it from someone who thought they couldn’t ever learn theory: the fundamentals of music theory, which you’ll use constantly in your playing, are surprisingly simple.

So what’s in a G chord? Well, the first thing you should know is that it contains the notes G, B, and D. The rule is that it must contain at least one of each of those notes and no others.

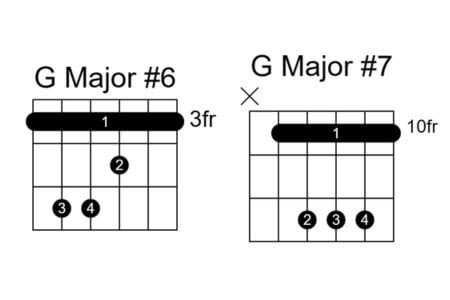

But how can a G chord only contain G, B, and D when we’re often strumming all six strings? It contains multiples of G, B, and D in different octaves. Let’s look at the classic G chord below:

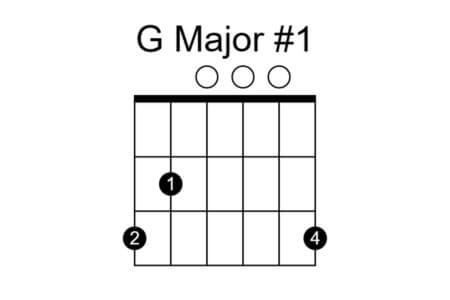

This is the shape most of us learn first, largely because it’s easy to fret and sounds great with three open strings ringing out. From lowest to highest pitch, the notes that sound are G, B, D (open), G (open), B (open), and G.

As you can see, the note G is sounded in three different octaves (bass, alto, soprano, if you will) with this chord voicing. The note B is also repeated, with the open string B sounding one octave higher than the B on the fifth string.

You have a lot of flexibility on the guitar to play the G chord in multiple ways across the fretboard, since the notes G, B, and D appear in many different places. There are literally dozens of ways to play a G chord!

Why Does a G Chord Have the Notes B and D?

We can accept that a G chord should contain at least one G, but why does it also have B and D?

The best way to address this question is to get into some basic music theory. A chord is a collection of notes derived from a scale of the same name. The G chord comes from the G scale. Using proper terminology, we might say that a G major chord (same thing as a G chord) is derived from the G major scale.

The G major scale consists of the notes G, A, B, C, D, E, and F#. Think of this as a musical alphabet, a group of notes that sound good together and center around G. When you hear a G major scale or a song in the key of G major, you hear G almost as a center of gravity. G feels like the home base. You’ll notice that most songs in G major end on a G chord.

But why B and D? Well, chords are built in thirds from the parent scale. You can think of a third as “every other” letter. In a G major scale, counting by thirds looks like this: G, B, D, F#, and so forth.

If you want to build a G major chord, you need two thirds on top of G. One third above G is B, and one third above that gets you to D. The distance from G to D is two thirds, which is also known as a fifth.

If you’re interested in learning theory and want some help getting started, head to my recommendations page to see my favorite books for beginners.

What's the Easiest Way to Play a G Chord?

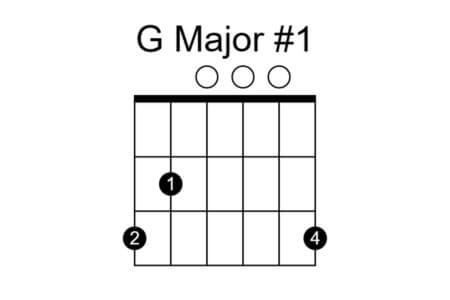

You don’t need to work hard to play a G chord on guitar. In fact, you can fret it with just one finger:

The only trick with this shape is that you can’t sound the lowest two strings. You need to either start your strum on the fourth string (easy way) or mute the low strings somehow (hard way).

Be assured that you’re not “cheating” by playing this version of the G chord. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with taking advantage of open strings, which is what makes this shape so easy to play. It sounds great and it works from a theoretical perspective—what more can you ask for?

Aren't the G Barre Chords Really Hard?

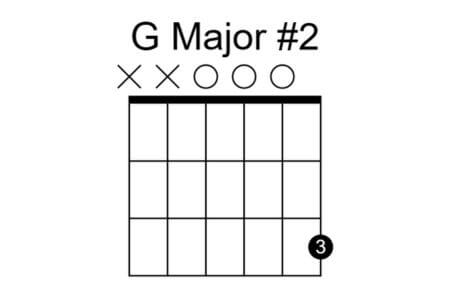

You’ll find the two most common G barre chords below:

In a way, these chords are definitely “hard.” Like all barre chords, they require you to press down on multiple strings with your index finger. This may be the hardest guitar technique in terms of sheer tension on the hand and fingers. However, barre chords can be made easier with practice! Check out this post for a bunch of ways to improve your barres.

In another way, barre chords are kind of easy. I know that may seem counterintuitive, but if you think about it, playing guitar would be a lot harder if we couldn’t use barre chords.

The reason is that barre chords are moveable. They work equally well starting on any fret, whereas open string chords only work in one position.

Let’s look at the G barre chord above on the left. It has you barring the third fret with your index finger, and that makes sense because the note on the third fret, sixth string is G. If we move the entire shape up one fret, we’ll be playing G# (or Ab). Move up another fret and we’ll have an A chord, and so forth.

This means that for every barre chord we learn, we really learn that same shape in every other key. We can move both of the above barre chord shapes up and down the neck to play any other major chord.

Why does this work? Well, as we move up or down the fretboard the identity of the notes change (G to G# to A, say) but the intervals between the strings stay the same. Any “major” barre chord shape can become any major chord depending on where you fret it.

Should You Know Multiple Ways to Play a G Chord?

To be honest, you don’t need to know more than one way to play the G chord on guitar. You could exclusively play the following one-finger G chord for the rest of your life:

There’s no “chord police” department (certainly not one that gets public funding). Musicians also tend to be chill people, so I doubt you’ll get much flak.

That said, if you want to push yourself to the next level, it won’t hurt you to know as much as possible. That includes knowing multiple ways to “voice” common chords. Having a bunch of chord shapes at your disposal will give you freedom to move about the fretboard and find the perfect sounding chord for your purposes.

Another reason to learn many G chords is that you’ll be able to make smoother connections. For example, if you’re playing a G-C-D progression and you’re planning on fretting a C chord at the 8th fret, you might want to use the G barre chord at the 10th fret instead of an open shape in 1st position to avoid a huge leap across the fretboard.

All of which boils down to this: don’t feel bad for what you don’t know, but also don’t be afraid to expand your horizons!

Conclusion

The beauty of the guitar is that it allows you to play virtually every chord in a ton of different ways. Of course, the downside of being spoiled for choice is that you might not know what to prioritize. Should you master 1st position chords before you learn them in 5th or 9th position? Is barring something you should seek out or avoid?

My two cents is that, generally speaking, you should always try to embrace new knowledge of the guitar. Ours is an intricate and delicate instrument, capable of everything from easy accompaniment to dazzling solos. It’s a tremendous amount of musical ground for six strings.

I hope you find these G chord shapes useful in your playing!

Are you looking to upgrade your gear or browse some awesome guitar learning materials? Check out my recommendations page to see all my favorite stuff.

Want to streamline your fingerstyle guitar progress? I just released my new ebook, Fingerstyle Fitness, which presents 10 easy exercises to quickly develop your fingerstyle chops. Grab it today!